The belief that digital means eternal is a dangerous illusion. Your collection is actively threatened by hardware failure, software obsolescence, and data decay. True preservation is not passive storage; it’s an ongoing battle that requires emulating old systems, hoarding obsolete hardware, and deploying active intervention strategies to maintain the life of an artwork. Without these urgent measures, the cultural artifacts of our time risk becoming unreadable ghosts in a decade.

As a collector or archivist, you’ve invested in the art of our time—works born from code, pixels, and electricity. There’s a comforting, yet dangerously false, sense of security in the digital. We assume that unlike a fading canvas or a crumbling sculpture, a file is forever. We hear the common advice to “back up your data” or “migrate to new formats” and believe we have built a fortress around our cultural assets. This is a critical misunderstanding of the enemy we face.

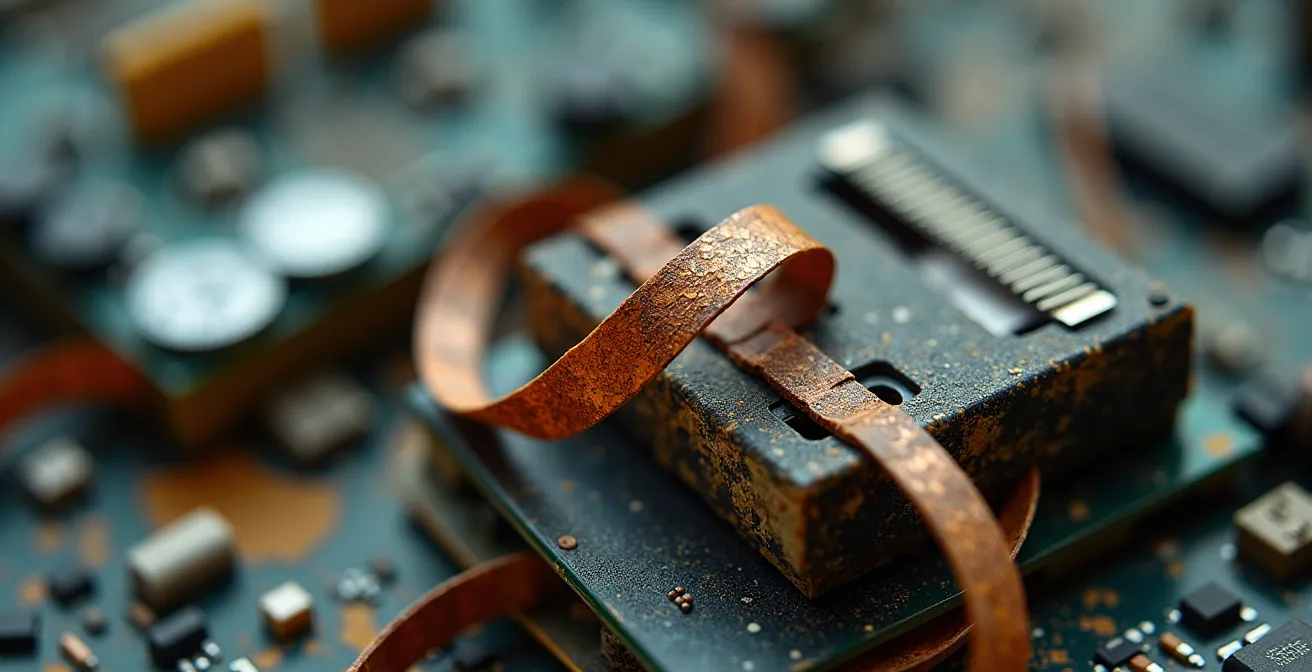

The threat isn’t a single catastrophic event; it’s a slow, silent decay. It’s the operating system that no longer runs the software, the custom hardware that has no replacement parts, and the very code of the artwork that becomes a foreign language to modern machines. The core problem is that we are trying to solve a dynamic challenge with static solutions. But what if the key to preservation wasn’t just in storing the files, but in recreating the entire world in which they were meant to live? The real work of a digital archivist is not just to save the object, but to preserve its very soul—its behavior, its context, its interactive experience.

For those who prefer a visual format, the following video offers an excellent primer on the complex challenges involved in ensuring the survival of digital art, perfectly complementing the strategies we are about to dissect.

This guide moves beyond simplistic advice to reveal the urgent, interventionist strategies required to combat the digital dark age. We will explore the active battle being waged in conservation labs to keep these vital works alive, from resurrecting obsolete software to preserving the authentic glow of a cathode-ray tube monitor.

Summary: A Survival Guide for the Digital Art Archivist

- Run or Rewrite: How to Keep 90s Net Art Alive

- The CRT Crisis: Why Old Monitors Are Gold for Museums

- Data Decay: Checking Your Archives Before It’s Too Late

- Recording the Click: Preserving the User Experience, Not Just the Code

- Hacking to Save: Breaking DRM to Keep Art Functional

- When VR Becomes the Only Way to Visit Endangered Heritage

- The Ghost Show: Preserving the Experience After the Doors Close

- The Immutable Ledger: Solving Art Forgery with Code

Run or Rewrite: How to Keep 90s Net Art Alive

For artworks born in the early, wild days of the internet, the original code is often inextricably linked to a specific, now-extinct digital ecosystem of browsers, plugins, and operating systems. Simply saving the HTML files is like preserving a musical score without any instruments. To truly keep the art alive, conservators face a critical choice: run the old environment or rewrite the artwork for a new one. This isn’t a simple technical decision; it’s a profound curatorial one. The path of strategic emulation has emerged as a leading solution, where a virtual machine is created to perfectly mimic the original hardware and software, allowing the artwork to run as the artist intended. This approach honors the work’s historical and technical specificity.

This methodology is part of a larger framework of preservation. For instance, the Variable Media Initiative pioneered by the Guggenheim Museum defines four core strategies: storage (preserving the bits), migration (updating the format), emulation (recreating the environment), and reinterpretation (re-creating the work’s effect with new technology). This gives institutions a vocabulary to define an artist’s acceptable boundaries for a work’s future life. The Guggenheim’s “Seeing Double” exhibition was a landmark case study, placing original media artworks alongside their emulated versions to question how authenticity is perceived and maintained across technological shifts. This proves that emulation isn’t a lesser copy but a sophisticated act of conservation.

The CRT Crisis: Why Old Monitors Are Gold for Museums

The concept of hardware authenticity is a critical battleground in digital art preservation. For many video and early computer-based artworks, the display technology is not a neutral window but an integral part of the piece. The specific flicker, phosphorescent glow, and color profile of a Cathode Ray Tube (CRT) monitor are inseparable from the artist’s intent. The move to flat-screen LCD and LED displays has created a preservation crisis: the unique visual qualities of CRTs are nearly impossible to replicate. This has turned obsolete, bulky monitors into priceless artifacts for museum conservation labs.

The scarcity of functional CRTs and the technicians who can repair them has become a global issue. Conservators are now in the business of stockpiling old televisions and monitors, and the few remaining specialists who can service this technology are in high demand. In a telling example, one technician in Minnesota has become a go-to resource for institutions worldwide; an industry report revealed that his client list now includes over 40 museums globally, all desperate to keep their video art collections viewable. This isn’t nostalgia; it’s the recognition that for artists like Nam June Paik or Bill Viola, the television set is as much the medium as the video signal itself. Preserving the monitor is preserving the artwork.

Data Decay: Checking Your Archives Before It’s Too Late

Beyond the visible crisis of obsolete hardware lies a more insidious threat: the slow, silent corruption of the digital files themselves. This phenomenon, known as data decay or bit rot, refers to the gradual degradation of storage media over time. Magnetic tapes demagnetize, CD-ROMs delaminate, and even hard drives can develop imperceptible errors that render a file unreadable. The digital object, which we perceive as immaterial, possesses a fragile digital materiality that demands constant vigilance. The longer a file sits unchecked, the higher the probability of its silent corruption. The urgency cannot be overstated; the digital world moves so fast that a file can become inaccessible not just through decay, but through simple software evolution.

Experts warn that the window of opportunity to act is alarmingly small. A crucial question to ask is: if you wrote a document 10 years ago, can you still open it? The complexity of software-based art, with its myriad dependencies, exponentially increases this risk. For a collector, this means that passive storage is a losing strategy. An active, cyclical process of monitoring, validating, and migrating data is essential. This involves not just creating backups, but regularly checking the integrity of those files (a process known as fixity checking) and having a clear plan for moving them to new storage media and formats before the old ones fail or become obsolete. Conservators now recommend that any medium upgrades should happen on a cycle of no more than five years.

Your Digital Preservation First-Aid Kit: An Audit Checklist

- Inventory and Identify: List every digital artwork in your collection. Document its file format, required software (including version numbers), and necessary hardware.

- Assess Carrier Risk: Identify all physical storage media (CD-ROMs, hard drives, USBs). Prioritize migrating files from older, higher-risk media first.

- Perform a Health Check: Use checksum tools (like MD5 or SHA-256) to create a digital fingerprint of each file. Periodically re-run the check to detect any data corruption or bit rot.

- Execute the “3-2-1 Rule”: Maintain at least three copies of your data, on two different types of media, with at least one copy stored off-site (or in the cloud).

- Document Everything: Maintain detailed metadata for each artwork, including its history, technical requirements, and any preservation actions taken. This log is as valuable as the artwork itself.

Recording the Click: Preserving the User Experience, Not Just the Code

What is a video game without the controller? What is an interactive net art piece without the lag of a 56k modem or the specific feel of a first-generation mouse? A critical frontier in digital conservation is the preservation of experiential integrity. This principle argues that the user’s interaction—the clicks, the navigation, the interface’s response time, and even its frustrations—are an intrinsic part of the artwork. Saving the source code is essential, but it captures only a blueprint of the work, not the living experience of it. The real challenge is to document and preserve the entire human-computer interaction.

To achieve this, archivists are moving beyond code repositories and adopting methods from ethnography and performance studies. This involves creating detailed documentation through video recordings of users interacting with the work on its original hardware. These recordings capture the nuances of interaction: the speed of the cursor, the sound of the hard drive, the way a user navigates a confusing menu. Conservators also write extensive descriptions of the “feel” of the piece and conduct interviews with the artists and original users to build a rich body of qualitative data. This documentation becomes a vital guide for future curators and technicians, enabling them to reconstruct the experience with a high degree of fidelity, whether through emulation or reinterpretation. It ensures that future audiences don’t just see the work, but understand how it felt to engage with it in its native time and context.

Hacking to Save: Breaking DRM to Keep Art Functional

Sometimes, the biggest threat to an artwork’s survival isn’t decay, but protection. Digital Rights Management (DRM) and other copy-protection technologies, designed to prevent piracy, can become a death sentence for digital art. When the company that holds the authentication key goes out of business, or the server that validates the software is shut down, the artwork can be rendered permanently inaccessible, even if the files are perfectly preserved. In these urgent cases, preservation requires a form of archival intervention that can feel more like hacking than curating. Conservators and computer scientists must often reverse-engineer software or “crack” its protection to liberate the artwork from its digital prison.

This is a complex ethical and legal area, but one that institutions are being forced to navigate. As Deena Engel, a professor at NYU’s Courant Institute of Mathematical Sciences, notes, “Digital works can be remarkably fragile because they usually depend on a specific set of software and hardware in order to be displayed as the artist envisioned. When operating systems change and software updates, it becomes much harder to preserve digital artworks.” This fragility is amplified by DRM. In response, pioneering collaborations like the joint project between the Guggenheim Museum and New York University have been established to preserve key digital artworks. Their work on pieces like Shu Lea Cheang’s *Brandon* (1998-99) and Mark Napier’s *net.flag* (2002) involves deep-diving into obsolete code and creating preservation strategies that often require bypassing the original, restrictive systems to ensure the works remain functional for future generations.

When VR Becomes the Only Way to Visit Endangered Heritage

The tools forged for preserving born-digital art are now being turned toward an even broader mission: saving our physical world from the ravages of time. Climate change, conflict, and natural decay threaten cultural heritage sites globally. In this context, technologies like 3D scanning, photogrammetry, and Virtual Reality (VR) are becoming essential archival tools, creating high-fidelity digital surrogates of objects and places before they are lost forever. This isn’t about replacing the original, but about creating a permanent, accessible record that can serve both scholarly research and public memory. For a future generation, a VR walkthrough of a lost temple may be the only visit possible.

Institutions like the Smithsonian are leading the way, using these techniques not just for documentation, but for active conservation. In a departure from traditional methods, the Smithsonian implemented 3D scanning and advanced digital photography on projects like the Gunboat Philadelphia. This technology allows for the real-time monitoring of minute areas of erosion and structural change, providing data that is impossible to gather with the naked eye. The resulting 3D models become a dynamic, evolving record of an object’s life and decay. This creates a “digital twin” that can be studied from anywhere in the world, democratizing access and creating new avenues for research, all while the fragile original is kept in a controlled, stable environment. It’s a powerful fusion of physical and digital conservation.

The Ghost Show: Preserving the Experience After the Doors Close

What happens when an exhibition ends? For traditional shows, a catalog and installation photos remain. But for exhibitions of digital, interactive, or virtual reality art, the experience itself is the main event. How do you archive an experience? This challenge has given rise to new models of curation and preservation, where the goal is to capture and maintain the entire ecosystem of a show long after its physical doors have closed. This involves archiving not just the individual artworks, but also their spatial relationships, the user interface for navigating the show, and the social context in which they were presented.

Pioneering institutions are emerging to tackle this directly. Since its founding in 2013, the Digital Museum of Digital Art (DiMoDA) has functioned as a virtual institution dedicated to commissioning and exhibiting VR-based artworks, creating shows that can be downloaded and experienced anywhere in the world. This model makes the exhibition itself the distributable, archivable object. Meanwhile, established museums are rapidly building their own collections of time-based media, which includes video, software, and internet art. The Metropolitan Museum of Art has assembled a collection of over three hundred such works since 1999, necessitating a dedicated conservation department focused solely on the unique challenges these pieces present. These efforts acknowledge that the ephemeral experience of an exhibition can, with the right strategy, be given a form of permanence, allowing the “ghost show” to be re-animated for audiences years later.

Key Takeaways

- Preservation Is Action: Digital art survival depends on active, ongoing intervention, not passive storage.

- Hardware Is Art: The original display and input devices (like CRT monitors) are often an inseparable part of the artwork and must be preserved.

- Experience Over Code: The goal is to preserve the user’s interaction and the ‘feel’ of the artwork, not just the underlying files.

The Immutable Ledger: A Tool for Provenance, Not a Preservation Panacea

In the conversation around digital art, blockchain technology and NFTs are often presented as a revolutionary solution to permanence. At its core, a blockchain is an immutable public ledger, excellent for creating a tamper-proof record of ownership and transaction history. This is a powerful tool against forgery and for establishing a clear chain of provenance. By minting an artwork as a Non-Fungible Token (NFT), an artist can create a unique, verifiable asset, solving the problem of infinite reproducibility that long plagued digital creators. This decentralized record, resistant to censorship and manipulation, provides a powerful new layer of security for the art market.

However, it is critical to distinguish between preserving provenance and preserving the artwork itself. An NFT is, in most cases, a token on a blockchain that points to a media file stored elsewhere on the internet. If that file corrupts, the link breaks, or the server hosting it goes down, the owner is left with an unbreakable certificate of ownership for an artwork that no longer exists. While some platforms are exploring on-chain storage, the standard archival mantra remains paramount. As archivists have long known, “lots of copies keep stuff safe,” and the standard for preservation-grade storage is ‘3 copies, in 3 locations.’ Blockchain can enhance this by adding cryptographic proof that the stored files are unaltered, but it does not replace the fundamental need for robust, redundant, and actively managed storage. The ledger can prove you own the ghost, but it cannot bring it back to life.

The evidence is clear: inaction is a choice for extinction. The responsibility to combat the digital dark age falls on those who steward these collections. The time to move from passive ownership to active preservation is now. Begin by auditing your collection, identifying the most at-risk works, and formulating a proactive conservation strategy. This is the only way to ensure the art of our time has a future.