Digital Arts

Digital art has fundamentally transformed how we create, collect, and experience visual culture. What began as experimental computer graphics has evolved into a sprawling ecosystem encompassing blockchain-based ownership, algorithm-driven creation, room-scale installations, and interactive experiences that respond to our presence. Unlike traditional art forms bound to physical materials, digital art exists as code, pixels, and light—ephemeral yet infinitely reproducible, challenging our very definitions of authenticity and value.

This transformation raises profound questions for artists, collectors, and institutions alike. How do we preserve artworks whose medium is constantly evolving? What does it mean to “own” something that exists only as data? How do immersive technologies change the relationship between viewer and artwork? This comprehensive exploration examines the technical, philosophical, and practical dimensions of digital art, from the algorithms that generate autonomous compositions to the neuroscience of multisensory perception.

What Defines Digital Art in Contemporary Practice?

Digital art encompasses any creative work that relies on digital technology as an essential part of its creation or presentation. This definition intentionally remains broad, spanning everything from digital paintings created on tablets to vast projection mapping installations that transform architectural facades into animated canvases.

The distinguishing characteristic isn’t simply the use of computers as tools—many traditional artists now sketch digitally—but rather works where the digital medium fundamentally shapes the artistic outcome. A photographer who scans film negatives uses digital tools; a generative artist who writes code that produces unpredictable visual compositions creates something possible only through computational processes.

Contemporary digital art practice generally encompasses several key domains:

- Generative and algorithmic art where code produces visual or sonic outputs

- Digital painting and illustration created with styluses and pressure-sensitive displays

- 3D modeling and virtual environments including immersive VR experiences

- Projection mapping and light installations that transform physical spaces

- Interactive and responsive artworks that change based on viewer behavior

- Net art and browser-based works designed specifically for online experience

- Crypto art and NFTs authenticated through blockchain technology

The boundaries between these categories remain deliberately fluid, with many contemporary artists combining approaches to create hybrid works that resist simple classification.

Digital Ownership and the Blockchain Revolution

The emergence of blockchain technology has addressed one of digital art’s most persistent challenges: establishing provenance and scarcity for infinitely reproducible files. Non-fungible tokens (NFTs) create cryptographic certificates of authenticity that track ownership through transparent, immutable ledgers.

From Physical Objects to Digital Possession

Traditional art collecting centers on physical custody—you own the canvas, the sculpture, the print. Digital art fundamentally disrupts this model. When you acquire an NFT artwork, you’re purchasing authenticated ownership rights while the actual image file may exist in countless identical copies across the internet. This shift challenges our intuitive understanding of possession, similar to owning a deed to property versus occupying the land itself.

This creates practical questions for collectors: How do you display digital art in domestic environments? Solutions range from dedicated digital frames with high-resolution screens to projectors that transform walls into dynamic galleries. Some collectors embrace the medium’s fluidity, rotating artworks daily, while others find the lack of physical presence psychologically unsatisfying.

Environmental and Economic Considerations

The crypto-art ecosystem faces legitimate scrutiny regarding its environmental footprint. Earlier blockchain networks consumed enormous energy through proof-of-work mining, though many platforms have since migrated to more efficient proof-of-stake systems that reduce energy consumption by over ninety percent. The conversation reflects broader tensions between technological innovation and ecological responsibility.

The digital art market also exhibits significant volatility, with valuations fluctuating dramatically based on cryptocurrency prices, collector sentiment, and platform stability. Unlike traditional art markets with established auction houses and gallery systems providing some price stability, digital art markets remain comparatively nascent and speculative.

Creating Digital Art: Algorithms, Code and Immersive Experiences

Digital art creation encompasses radically different methodologies, from intimate laptop-based practices to elaborate installations requiring engineering teams and specialized hardware.

Generative Art and Algorithmic Authorship

Generative art inverts the traditional creative process. Rather than directly producing a final image, artists write algorithms that autonomously generate artworks according to programmed rules and random variables. The artist becomes a system designer, establishing parameters while surrendering precise control over outcomes.

Consider a generative piece that creates abstract compositions based on real-time weather data: the artist codes the relationship between temperature, humidity, and color palette, but each instantiation produces unique results. This raises fascinating questions about authorship—who creates the art, the programmer or the algorithm?

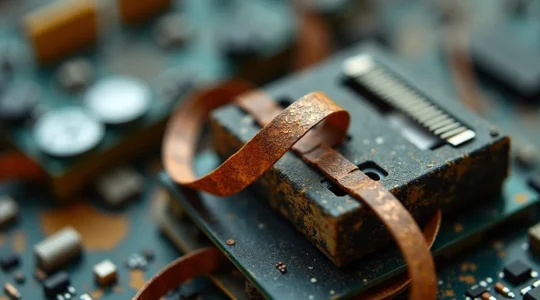

Immersive Public Installations

Large-scale digital installations transform public spaces through coordinated light, sound, and projection mapping. These experiences require sophisticated technical infrastructure: high-lumen projectors, precise geometric calibration to map imagery onto irregular architectural surfaces, and robust audio systems capable of spatial sound design.

Creating immersive experiences presents unique challenges:

- Technical execution: Synchronizing multiple projectors and audio channels while compensating for ambient light and environmental acoustics

- Safety management: Controlling crowd flow, preventing trampling risks, and ensuring electrical systems meet regulatory standards

- Legal compliance: Securing permission to project onto buildings, particularly those with copyright-protected architectural designs

- Narrative coherence: Crafting compelling stories without linear structure, allowing viewers to enter and exit at any point

The best immersive works balance technical spectacle with emotional resonance, using audio spatialization—placing sounds in three-dimensional space around listeners—to create enveloping sensory environments that transcend passive observation.

Preserving Digital Art for Future Generations

Digital art conservation confronts a paradox: while digital files theoretically last forever, the systems needed to display them become obsolete within years. A digital artwork from the early internet may require software that no longer runs on modern operating systems, displayed on hardware no longer manufactured.

The Obsolescence Challenge

Technological obsolescence manifests in multiple forms. Software dependencies disappear when companies cease support or platforms shut down. Hardware failures become irreparable when replacement components no longer exist—try finding a functional CRT monitor with specific phosphor characteristics essential to how a work from the nineties was meant to appear.

Even when hardware survives, bit rot—the gradual corruption of digital files through storage media degradation or data transfer errors—silently destroys artworks. A single corrupted bit in executable code can render an entire interactive piece non-functional.

Preservation Strategies

Conservators employ two primary approaches to combat obsolescence:

- Emulation: Creating software that mimics obsolete hardware or operating systems, allowing original code to run on contemporary computers. This preserves the authentic code but requires ongoing emulator development.

- Migration: Rewriting artwork code for current platforms, maintaining functionality while potentially altering subtle behaviors. This ensures accessibility but raises authenticity questions.

Both strategies require meticulous documentation of the artwork’s intended “performance”—how it should look, sound, and respond to interaction. This documentation itself becomes an artwork component, as essential as the code.

Legal complexities further complicate preservation. Copyright law may technically prohibit the code modifications necessary for conservation without explicit artist permission, creating situations where artworks cannot legally be saved from obsolescence.

Interestingly, some artists embrace technological decay as aesthetic choice, creating works intentionally designed to degrade or become inaccessible as their original platforms disappear—digital art as fundamentally temporal, challenging preservation’s very premise.

How We Experience Digital Art: Perception and Interaction

Digital art frequently transforms viewers from passive observers into active participants, fundamentally altering the psychological and neurological dimensions of aesthetic experience.

The Neuroscience of Multisensory Immersion

Immersive digital installations engage multiple sensory channels simultaneously—visual, auditory, sometimes haptic—in ways that traditional artworks rarely attempt. Neuroscience research reveals that multisensory integration activates different brain regions than viewing static images, creating more intense emotional responses and stronger memory formation.

However, this intensity carries risks. Sensory overload in poorly designed installations can trigger cognitive fatigue, anxiety, or disorientation. The most effective immersive works carefully calibrate stimulus intensity, providing rhythm and variation rather than constant bombardment.

From Observation to Participation

Interactive digital art collapses the boundary between artwork and viewer. Motion-tracking systems respond to your gestures, generative compositions evolve based on your choices, virtual reality places you inside the artwork itself. This participatory dimension creates co-authorship—the work doesn’t fully exist until activated by viewer interaction.

Emerging haptic technologies promise even deeper immersion, using vibration, force feedback, and temperature changes to create tactile experiences in visual art. Imagine feeling the texture of a virtual sculpture or sensing the warmth of digital light—technologies currently in development that may soon expand digital art’s sensory vocabulary.

Digital Art in the Viral Age

Social media has created new distribution channels and aesthetic forms, from GIFs designed for infinite loops to glitch art optimized for smartphone screens. Yet this accessibility creates ephemerality—digital artworks achieve viral visibility then vanish into algorithmic archives within days. This fleeting nature mirrors contemporary attention economies, where cultural moments burn intensely but briefly.

Digital Design: Where Art Meets Communication

The boundary between digital art and digital design remains productively ambiguous. Both share technical foundations and visual languages, yet diverge in intention—design serves communication goals while art pursues aesthetic or conceptual exploration. Contemporary practice increasingly blurs these distinctions.

The Evolution of Visual Communication

Digital visual language carries DNA from print-era design traditions. The grid systems that structure websites descend directly from Swiss Style modernism of the mid-twentieth century. Typography principles developed for letterpress persist in screen-based design, though digital displays introduce new considerations around legibility at various resolutions and pixel densities.

Color psychology operates differently across contexts—branding color choices prioritize recognition and emotional association, while artistic color usage explores perception, cultural meaning, and compositional relationships. The same blue might signify corporate trustworthiness in a logo and melancholic introspection in a digital painting.

Contemporary Trends and Ethical Questions

Digital media exhibits cyclical aesthetic trends, with retro aesthetics regularly resurging. Early internet visual language, pixel art, vaporwave nostalgia—each mines previous technological eras for stylistic elements, remixing obsolete formats into contemporary expression.

Typography continues evolving for screen optimization, with variable fonts allowing single typefaces to fluidly adjust weight and width, improving legibility across devices from smartwatches to large displays. These technical innovations expand expressive possibilities while solving practical reading challenges.

Perhaps most critically, designers working in digital contexts face ethical responsibilities around persuasive design. When interfaces use psychological principles to maximize engagement or manipulate behavior, the line between effective communication and exploitation grows thin. This ethical dimension increasingly concerns practitioners who recognize their work’s power to shape attention and action.

Digital arts represent an ever-expanding frontier where technology and creativity intersect, challenging traditional boundaries while establishing new aesthetic vocabularies. Whether exploring blockchain authentication, preserving code-based artworks, or designing immersive experiences, practitioners navigate technical complexity while pursuing timeless artistic goals: meaning-making, emotional resonance, and expanding human perception.

Why Your Modern App Interface Still Follows Rules Set in the 1920s

Contrary to the belief that digital design is a new frontier, its core principles are a direct philosophical inheritance from a century ago. The minimalist aesthetic, grid systems, and functional typography you use daily are not modern inventions but a…

Read more

Why Immersive Art Exhibits Leave You Exhausted Instead of Inspired

Contrary to the belief that immersive art offers a deeper connection, it often engineers ‘cognitive burnout’ by deliberately overwhelming our brains. These exhibits weaponize sensory overload (lights, sound) to hijack our limited attention, preventing deep thought. Their “Instagrammable” nature creates…

Read more

Why Your Digital Art Collection Might Disappear in 10 Years

The belief that digital means eternal is a dangerous illusion. Your collection is actively threatened by hardware failure, software obsolescence, and data decay. True preservation is not passive storage; it’s an ongoing battle that requires emulating old systems, hoarding obsolete…

Read more

How Projection Mapping Turns Buildings into Living Canvases

Turning a skyscraper into a canvas is less about the power of the projector and more about mastering the complex engineering of geometry, safety, and human perception. Precision mapping requires creating a digital twin of the architecture, treating every window…

Read more

How to Collect Art That Doesn’t Exist in the Physical World

Collecting digital art is not a departure from tradition but its technical evolution, translating core principles of provenance, curation, and preservation into a new code-based framework. Provenance is no longer a paper trail but an immutable, publicly verifiable history recorded…

Read more