Blog

Art shapes how we understand ourselves and the world around us, yet many people feel intimidated by museums, uncertain about interpretation, or disconnected from their own creative potential. The relationship between humans and visual culture spans experiencing masterpieces in galleries, decoding symbolic language in paintings, questioning what deserves to be called art, understanding the physical demands of craftsmanship, and recognizing creativity’s profound impact on mental well-being.

This resource connects these diverse threads into a cohesive understanding of how art functions in our lives. Whether you’re planning your first museum trip, trying to make sense of contemporary installations, considering a creative career, or simply curious about why certain images move you, the foundations explored here will transform passive observation into active, meaningful engagement with visual culture.

Experiencing Art in Person: Museums, Galleries, and Cultural Travel

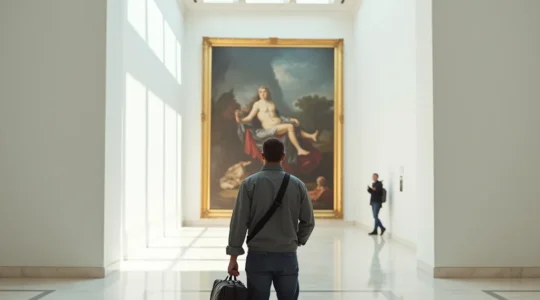

Viewing art in its original context creates a fundamentally different experience than seeing reproductions in books or on screens. The scale, texture, and spatial presence of a work can only be fully appreciated when standing before it, which is why art-focused travel has become an essential practice for anyone serious about understanding visual culture.

The Psychological Impact of Authentic Encounters

Research consistently demonstrates that viewing original artworks triggers stronger emotional and cognitive responses than reproductions. The knowledge that you’re in the presence of the actual object an artist touched centuries ago creates a temporal bridge that digital images cannot replicate. This phenomenon explains why pilgrimage-like visits to major collections remain valuable despite universal digital access to high-resolution images.

Planning Museum Visits Strategically

Effective museum visits require more than simply showing up. Consider these practical approaches:

- Research collection highlights beforehand to prioritize must-see works during peak alertness

- Schedule visits during off-peak hours (typically weekday mornings) to reduce crowd fatigue

- Limit yourself to specific galleries rather than attempting comprehensive coverage, which leads to museum exhaustion

- Alternate between guided tours for historical context and independent exploration for personal discovery

The sequence of your visits matters more than many realize. Viewing works in historical chronology helps you understand artistic evolution, while thematic groupings reveal how different cultures approached similar subjects.

Reading Visual Language: How to Interpret What You See

Every painting, sculpture, or photograph employs a visual grammar that guides your eye and constructs meaning. Learning to read this language transforms confusion into comprehension, revealing intentional choices that might otherwise seem arbitrary.

Compositional Techniques That Guide Perception

The rule of thirds divides an image into a 3×3 grid, with points of intersection creating natural focal areas where the eye instinctively lands. Artists use this framework (or deliberately violate it) to control viewer attention. Similarly, diagonal lines create movement and energy, while horizontal lines suggest stability and calm.

In portrait painting, the direction of a subject’s gaze and gesture implies relationships between figures and invites you into specific narrative interpretations. A hand pointing toward another character or an object establishes visual connections that tell stories without words.

Symbolism and Narrative Codes

Historical art operates through a shared vocabulary of symbols that contemporary viewers often miss. A dog in a Renaissance portrait typically represents fidelity, while skulls remind viewers of mortality. Understanding these iconographic conventions unlocks layers of meaning that would otherwise remain invisible.

Medieval art frequently employed continuous narrative techniques, showing the same figure multiple times within a single composition to depict sequential events. Recognizing this convention prevents the confusion of seeing what appears to be identical twins when it’s actually the same character at different moments in a story.

What Counts as Art? Philosophy and Institutional Critique

The question “what is art?” has no settled answer, and the ongoing debate shapes everything from museum acquisitions to tax law. Understanding these philosophical tensions helps you navigate contemporary art that might initially seem baffling or provocative.

The Readymade and Authorial Intent

When Marcel Duchamp placed a urinal in a gallery and called it art, he fundamentally challenged the assumption that art requires manual craftsmanship or aesthetic beauty. The readymade concept suggests that artistic value emerges from the artist’s selection and contextual framing rather than technical skill. This radical idea still generates controversy more than a century later.

Institutional Power and Validation

Museums, galleries, and critics function as gatekeepers who legitimize certain objects as art while excluding others. This institutional role creates circular logic: art is what institutions display, and institutions display what they’ve defined as art. Performance art and dematerialized conceptual work challenge this system by creating experiences that cannot be collected or sold, questioning whether the art market itself corrupts creative expression.

Legal battles over art classification often hinge on practical concerns like tax deductions for donations or import duties. These cases force courts to define art through criteria that philosophers have debated for millennia, demonstrating how abstract questions have concrete financial consequences.

The Physical Reality of Making Art: Craft and Practice

Behind finished artworks lies a physical practice that most viewers never consider. Understanding the bodily dimension of creative work reveals why certain techniques developed, what constraints artists navigate, and how craft knowledge transfers across generations.

Muscle Memory and the Flow State

Repetitive craft develops muscle memory that allows artisans to execute complex techniques without conscious thought. A experienced potter’s hands know the exact pressure needed to center clay, while a calligrapher’s arm moves through letterforms automatically. This embodied knowledge cannot be fully captured in written instructions, which is why apprenticeship remains essential for many traditional crafts.

The psychological state of “flow” occurs when skill level perfectly matches task difficulty, creating periods of timeless absorption where hours pass unnoticed. Artists and craftspeople often describe this state as the primary reward of their practice, more meaningful than external recognition or financial compensation.

Occupational Realities and Adaptation

Traditional workshops involve genuine occupational hazards: repetitive strain injuries, exposure to toxic materials, respiratory problems from dust or fumes. Understanding these physical costs adds dimension to your appreciation of hand-crafted work. As artisans age, they adapt tools and techniques to accommodate changing bodies, demonstrating how craft practice evolves through the lifecycle.

The tactile sensitivity in craftspeople’s fingertips develops through years of practice, allowing them to detect subtle variations in texture, temperature, and resistance that guide their work. This sensory refinement represents a form of expertise that industrial production cannot replicate.

Living and Working as an Artist Today

Professional artistic practice involves far more than creating work. Artists must develop business skills, navigate complex representation systems, and maintain creative output despite frequent rejection and financial precarity.

Building a Coherent Professional Identity

A strong artist statement articulates your conceptual concerns, process, and influences in clear language that helps curators, c

Why Humans Must Create: The Biological Drive for Art?

Contrary to the popular belief that art is a mere skill or decorative hobby, it is a fundamental biological imperative hardwired into our species for survival. This drive is not about talent but is an essential cognitive tool for processing…

Read more

Why Talent Is Only 50% of a Successful Art Career

The “starving artist” myth is built on a lie: that talent is all that matters. A successful art career is not about waiting to be discovered; it’s about proactively managing your art practice as a business. Your artwork is a…

Read more

Is It Safe to Eat Off Your Grandmother’s Antique Plates?

The safety of vintage dishware is not a simple yes/no question; it’s a complex risk assessment of hidden chemical and physical dangers that go far beyond lead. Acidic foods (like tomato sauce or citrus) can leach heavy metals from unstable,…

Read more

Why the Body of a Master Artisan Fails After 40 Years of Labor

The neurological mastery defining a great artisan is the very mechanism that triggers their body’s inevitable collapse over a 40-year career. Decades of repetitive motion create a “somatic debt” of micro-traumas, leading to chronic conditions like Repetitive Strain Injuries (RSIs)….

Read more

Is It Art If I Just Sign It? The Legacy of Duchamp’s Urinal

The artistic value of an object like Duchamp’s urinal lies not in its physical creation, but in the conceptual and institutional framework that validates it as art. The act of selecting and re-contextualizing an object can be a more powerful…

Read more

How to Read a Painting Like a Novel from Left to Right

In summary: Treat a painting not as a single image, but as a directed narrative with a beginning, middle, and end. Artists use a “visual syntax” of light, gaze, and composition to control where you look and in what order….

Read more

How to Plan an Art Pilgrimage That Transcends Standard Tourism

Contrary to popular belief, a meaningful art pilgrimage isn’t about seeing more, but about seeing deeper. This guide moves beyond crowded museums and generic itineraries to reveal a strategic approach. You’ll learn how to choreograph your journey for maximum context,…

Read more